The catch 22 that led to ICU

This is an extended version of my story that ran in The Saturday Paper 19/11/16

In the ambulance, Katelyn wondered if she was having another psychotic episode. She could hear the ECG monitor and she thought it was emitting a long, drawn-out tone. For the past eight weeks she’d been told her heart could stop at any moment. Was this it?

By now she couldn’t stand in the shower without running out of breath. Her skin was yellow and her nails were rotting. It hurt to move, because the muscle and tissue that protected her organs from her bones was deteriorating. Going to the toilet was agony. Her liver and kidneys were shot.

After one night in the emergency ward of a Melbourne hospital, she was discharged. Katelyn was dying, but she was refusing care and she was deemed too high-risk to be sectioned.

“No one thought she would survive,” says Katelyn’s mother. “She was 37 kilos. Her words were jumbled and her movement was like that of an old lady. Everything was failing and there was nothing I could do.”

How had an eighteen-year-old girl become so desperately sick? Katelyn was locked in a catch 22. She was anorexic, but an eating-disorder ward will not admit someone withdrawing from drugs. She was dependent on ice, but many detox units will not admit someone below a certain BMI.

It’s easy to understand why. The two services operate as separate silos. Without the knowledge of combined care, whichever service accepts the patient could let them die from negligence. A patient with comorbid problems is unpredictable, perhaps even psychotic. The effects of the drug masks the severity of the eating disorder, and vice versa. A feeding tube will be needed. There may be cardiac arrhythmia. An emaciated body may not withstand withdrawal from drugs, nor the medications used to facilitate it.

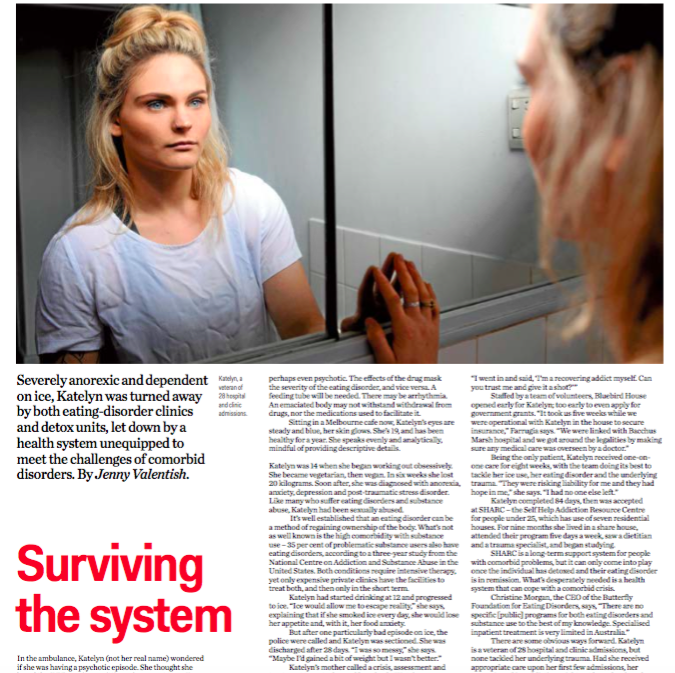

Sitting in a Melbourne café now, Katelyn’s eyes are steady and blue, her skin glows. She’s 19, and has been healthy for a year. She speaks evenly and analytically, mindful of providing descriptive details. She’s talking to The Saturday Paper to highlight the fact that if Australia’s health services don’t better integrate, people with comorbid problems will bounce from pillar to post until their condition is so severe that no one can take them at all.

The common factor beneath many eating disorders and problematic substance use is trauma. Katelyn was persistently sexually abused as a child. At fourteen, she trained her attention on something else: the gym. Working out became a welcome obsession, and she was pleased to drop 20 kilos in six weeks. She became vegetarian, then vegan.

“Mum realised my eating was a problem when she offered me a wrap with spinach and tomato in it. I chucked it at her, saying, ‘Don’t you dare give me food!’” Katelyn recalls. “I had blue lips and she thought for weeks I was wearing blue lipstick.”

Soon after, at the Royal Children’s Hospital, Katelyn was diagnosed with anorexia, anxiety, depression and PTSD. “I was tube fed. I was in wheelchairs. I learned a lot in the wards. I watched girls put things in their pockets and scrape butter off bread. I’d rub the soup Mum gave me into the wooden table. I got kicked out of home at 16 because I became violent, which was a tactic I’d learned to avoid eating.”

It’s well established that an eating disorder can be a method of regaining ownership of the body. What’s not as well-known is the high comorbidity with substance use – 35 per cent of problematic substance users also have eating disorders, according to a three-year study from the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. The shared risk factors are low self-esteem, depression, anxiety; unhealthy parental behaviours and a history of abuse or neglect. Both conditions require intensive therapy, despite which there will be high relapse rates. Yet only expensive private clinics have the facilities to treat both, and then only in the short term.

Katelyn had started drinking at 12 and progressed to ice. “For one night, ice would allow me to escape reality,” she explains. “When I had that realisation I’d go for four-day weekends. Then for the following three days of coming down, my eating disorder would rise up and I’d be depressed and anxious.” She realised that if she smoked ice every day, she would lose her appetite, and with it, her food anxiety.

“Within a year ice took me to being someone awful,” she says. Her housemates started out as friends, but their patience wore thin. Once kicked out, she was homeless. One day she returned to the house, agitated. The police were called and Katelyn was sectioned at another Melbourne hospital, then discharged after 28 days. “I was so messy. Maybe I’d gained a bit of weight but I wasn’t better.”

After a worrying phone call with her daughter, Katelyn’s mother called a crisis, assessment and treatment (CAT) team to do a welfare check. “Katelyn was difficult to engage with and I didn’t know if it was the drugs or the anorexia that had more of the control,” her mother recalls. “She was living in another reality and nothing made sense. We were all the enemy and trying to help her was perceived as harmful.”

She gave her daughter an ultimatum: voluntarily check in to a private psychiatric clinic’s ICU or go back out on the streets and lose her remaining family. Katelyn accepted, but upon being discharged from ICU she would need to stay off ice for two weeks to be admitted to its rehabilitation program. She had nowhere to go; not even a car to sleep in, since it had been stolen by her dealer.

“I kept telling everyone to let me die because I didn’t want to fight it anymore,” says Katelyn. “I just thought, I’m done.”

That’s when Wilson called Amber Farrugia, the founder of Bluebird House, a rehabilitation centre on the outskirts of Bacchus Marsh that was not yet operational. Farrugia had first-hand understanding of the dual diagnosis predicament, having previously been a drug and alcohol support worker at a private clinic. “There was a constant stream of people there with comorbid problems, either mental health or an eating disorder,” she recalls. “No one’s a straight ‘addict’; it’s complex.”

Farrugia confirms that Katelyn was expected to die. “That’s what the parents were told. I went in and said, ‘I’m a recovering addict myself. Can you trust me and give it a shot?’”

Bluebird House opened early with a team of volunteers; too early to even apply for government grants. “It took us five weeks while we we operational with Katelyn in the house to secure insurance,” says Farrugia. “We were linked in with the Bacchus Marsh hospital and we got around the legalities by making sure any medical care was overseen by a doctor.”

Being the only patient, Katelyn received one-on-one care for eight weeks, with the team doing its best to tackle her ice use, her eating disorder and the underlying trauma. The intensity of it moved Katelyn to run away three times. “I always came back,” she says. “They were risking liability for me and they had hope in me. I had no one else left.”

Katelyn completed 84 days, then got accepted at SHARC – the Self Help Addiction Resource Centre for people under 25, which has use of seven residential houses. For nine months she lived in a share house, attended their program five days a week, saw a dietician and a trauma specialist, and began studying. It’s fair to say she blossomed.

SHARC is an invaluable long-term support system for people with comorbid problems, but it can only step up once the individual has detoxed and their eating disorder is in remission. What’s desperately needed is a health system that can cope with a comorbid crisis.

Christine Morgan, the CEO of the Butterfly Foundation for Eating Disorders, says, “There are no specific [public] programs for both eating disorders and substance use to the best of my knowledge. Specialised in-patient treatment is very limited in Australia.” It’s hard enough, she says, for individuals struggling with an eating disorder alone. “The 2012 Paying the Price report surveyed Australians with a lived experienced of eating disorders treatment and 85 per cent found it ‘difficult to very difficult’ to access treatment.”

Morgan believes the answer lies in a connected health system that supports an individual for months, even years. “Eating disorders are complex mental illnesses that require multi-disciplinary teams of specialists all working together for one patient,” she says.

Dr Nadine Ezard, clinical director of the alcohol and drug service at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, sees the fall-out of fragmented care on a daily basis. She’s holding out hope for Primary Health Networks that are being set up around the country as a way of supporting general practices, including nurses and NGOs. “It’s about bringing those primary, secondary and acute-care services together,” she says.

There are some obvious ways forward. Katelyn is a veteran of 28 hospital and clinic admissions, but none tackled her underlying trauma. Had she received appropriate care upon her first few admissions, her coping mechanisms of anorexia and ice may not have developed.

Perhaps for comorbid cases, eating-disorder facilities could receive extra funding to have access to medical experts that can oversee clients who also need to withdraw. At present, individuals such as Katelyn are sometimes advised by their GPs to play down their drug use when approaching eating-disorder clinics; such as only admitting to weekend use, say. With this in mind, many wards are already dealing with drug withdrawal, even if inadvertently.

In the meantime, funding of the Butterfly Foundation’s telephone line continues to be uncertain after the Federal Government announced a streamlining of mental health services. Things are equally dire for Bluebird House, which is closed. The board is in the process of fundraising and is discussing the possibility of partnering with other organisations. Farrugia is determined the facility will reopen to provide care for people experiencing comorbid problems.

There’s better news for Katelyn, at least. She now lives in an apartment with her boyfriend and works as a swimming teacher. She’s still enrolled in SHARC’s program and also attends 12-step groups. She’s determined to speak for those people still falling between the cracks.

“If you’ve got bipolar and drug addiction, somewhere will take you,” she points out. “When it’s an eating disorder no one will. But where are those people going to go?”