Interview: Jenny Valentish on Evenings with Dominic Knight (transcript)

Cherry Bomb is Book of the Week on Evenings with Dominic Knight

Not every debut novel has effusive praise from Paul Kelly and Tim Rogers on its cover, but it’s not all that surprising when it’s been written by one of Australia’s most experienced music journalists.

It’s the story of Nina Dall, who starts a band called The Dolls with her cousin Rose, and finds herself burnt out and cynical by the age of twenty-one. And it raises thorny questions about the way power and sex operate in the music world, an industry dominated by middle-aged men, but which fetishises youth and beauty above all else.

Nina develops a complex relationship with super-producer John Villiers, and that’s before her industry legend aunt Alannah enters the frame, first as a source of advice but increasingly as a competitor…

JENNY: We start when she’s seventeen years old. A lot of times when you interview a rock star they’ve been crystallised at that age anyway. They could be in their forties, but they’re still trapped in amber at that age. I was thinking about if you’re a songwriter, can you really afford to fix what’s wrong with you? Because people pay to hear your songs about remorse and suffering, and they pay to see you fall off stage. I wanted to focus on somebody who’s got those sort of problems and have her mull over the quandary of getting sober and sorting herself out.

DOMINIC: It’s really interesting, isn’t it? Because we as fans romanticise these musicians who go and live outside the normal margins of life, and in a sense it gives Nina the inspiration for songwriting, but it makes for quite a difficult life.

JENNY: Well exactly. If you or I took three grams of coke and came into work it would be frowned upon, but for somebody in Nina’s position that’s expected of you, isn’t it?

DOMINIC: Yeah, and you get surrounded by enablers in a sense.

JENNY: There’s a great book written about the Runaways by Evelyn McDonnell [click here for my interview with Evelyn]. I wouldn’t say it informed Cherry Bomb, but there are parallels. It describes these fifteen-year-old girls who are surrounded by svengali figures, be it Kim Fowley, their manager, or producers and tour managers. They are fed drugs and fans are very keen to load you up with drugs to get you onside, so it would be a hard industry to stay sober in.

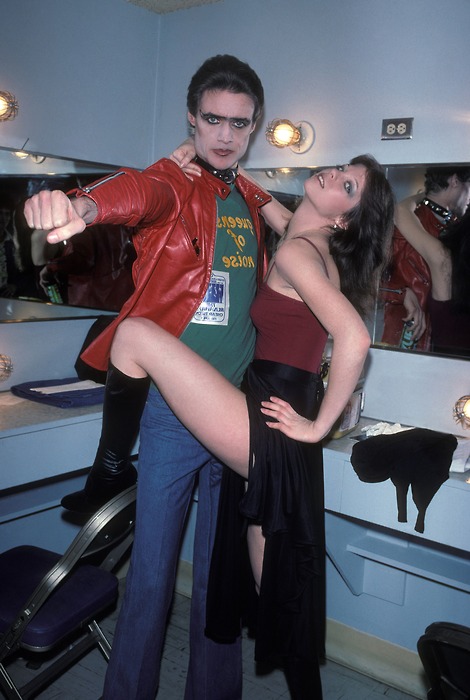

Kim Fowley and Runaway Jackie Fox

DOMINIC: Absolutely, and this is one of the interesting things about Cherry Bomb – you’ve got all these intense relationships going on, for instance, Nina’s bandmate Rose is her cousin, so there is all sorts of personal baggage there to begin with. Why did you decide to make two bandmates related?

JENNY: It was partly because I’m a music journalist and when I interview bands that have been around for a while, they’ve got this codependent relationship where they’re absolutely stuck – but they’ve got to work together if they want to continue their career. But they quite patently obviously hate each other. So there’s that underlying conflict that was quite irresistible when it came to writing a novel. But there’s also a darker side to it that isn’t immediately obvious when you look at the book – which is about child sexual abuse… and rock’n’roll! So I wanted to have two teenage girls who had very different experiences growing up, so you could see one almost like a control group and one person going off the rails.

DOMINIC: And there is a lot of darkness in Cherry Bomb. You’ve also given Nina an aunt who is a bit of an industry legend. She dispenses helpful advice in a mentoring role, but then that shifts as the novel goes on as well.

JENNY: Alannah Dall had a career in the ’80s and I was really fascinated by memoirs that I’ve read, people like Kate Ceberano, Chrissy Amphlett, Stephen Cummings, Don Walker, James Freud, all wrote about this time when there was a lot of money being thrown around. Way more than you could dream of now. You could easily drop a million bucks to record a record [update: flagrant exaggeration on my part… let’s say a half a mill going by some examples in Mark Opitz’s memoir Sophisto-Punk] or fly in a sitar player. So I wanted to juxtapose that era with the DIY, crowdfunding era we find ourselves in now. But there’s also conflict because as Alannah mentors the girls, she sees opportunities that she could be grabbing for herself.

Alannah Dall or Bananarama? Bananarama, but you get the idea.

DOMINIC: The old creative tension between the veteran and the young, hot band! But in terms of contrast in past and present, you’ve littered the novel with references to social media, so in that sense it’s very contemporary. I got a big sense of how the music industry works now.

JENNY: I had to do a bit of internet stalking. I looked at some contemporary pop stars – their profiles on Instagram and Twitter… things that I wouldn’t normally have bothered looking at, just to see what kind of interactions they had with their fans and how intense they are. And how you’re being constantly surveyed and stalked. I also ran the book past a pop star friend of mine – somebody who’d been through the mincing machine – and I ran it past a tour manager. I made sure it was all plausible.

DOMINIC: You’ve also created various social media profiles. Nina has a Twitter account; Rose has a Pinterest board on which she has pinned up a lookbook, and there’s a Spotify soundtrack as well, so you’ve clearly thought about how to extend the world of The Dolls into a social media space as well. Perhaps novelists have to do it the same way bands have to.

JENNY: I don’t know if he started it, but Chris Lilley certainly pioneered that when he started Summer Heights High. He had Twitter accounts for Ja’mie and all the characters. That really took off, and in the period where I was writing the book I thought, I don’t know how this is going to go – if it’s going to sink without a trace, if it’s going to do moderately well, or if it’s going to take off, but why don’t I set these things up right now?

DOMINIC: It seems like you’ve had a lot of fun with the output of The Dolls, coming up with lyrics and names of songs. Have you ever been in a band yourself?

JENNY: Yeah, I was in two in my twenties and I definitely drew quite a lot on them – up to the point that The Dolls get signed, a lot of the experiences were my own. One was an indie-ish band a bit like Sleeper and we really had our eye on the prize. Our singer would tell us before most shows, “There are going to be A&R scouts from EMI and Sony,” which may not have been true, but that was the pace we were operating under. I’d drop to my knees at a certain point in the song and try and make it look really natural. We’d wear matching shirts in the style of Manic Street Preachers. By contrast the other band was a surf band: all grass skirts, leis and mucking around on stage.

DOMINIC: There are so many things that sparked memories for me… I particularly loved the band name brainstorming. Every band has an embarrassing first name that would never have worked out. Midnight Oil, for instance, were called The Farm back in the day. You’ve given The Dolls one as well.

JENNY: The Dolls itself is pretty terrible, but I came up with some even worse ones, like The Bain Maries and The Vignettes, that kind of thing. A lot of the lyrics are my own teenage lyrics as well.

DOMINIC: It’s interesting the way you’ve chosen to have two young women in the band in what is mainly a male world with all kinds of men – and that too creates some tension. There’s a sexual dynamic that wouldn’t be there if it was a typical band of four young guys.

JENNY: Well no, and The Dolls use that to their advantage. The protagonist, Nina, is very sexually precocious, but also they’re teenagers and at that age when you’re a teenage girl – and maybe this happens to teenage boys, I don’t know – you get to this point where you realise that you have this power and the whole world opens up in front of you. You can use it for good or evil. In their case, they’re thinking that they have this control over the men around them… which to an extent they have, but perhaps not to the point that they think they have.

DOMINIC: There’s a really interesting power dynamic and in a sense, sex, power and career get blended in together for them.

JENNY: They set out to seduce the veteran producer, who’s been around for decades. That’s based on my first band: when we went into the studio we were just recording a single over one day. It was with this producer called [redacted] who had worked on The Cure, Neneh Cherry and lots of post-punk bands, and I just remember thinking there was a really interesting dynamic; an older man at the controls who holds your career in the palm of his hand. In actual fact, I spent most of the day the opposite end of the studio worried that I was going to get busted for not being very good at playing, but I did think if we were there for longer, would I try and manipulate this situation? And I thought yes, I probably would.

DOMINIC: One of the interesting things about how you’ve chosen to write the novel is that Nina speaks to us from the present, previewing what happened. So she’ll say something like “I didn’t know at the time this would become a famous conversation.” Why did you chose to structure the narrative in that way?

JENNY: Because I would have been writing from the point of a seventeen-year-old girl otherwise, and this way I was able to write from the point of view of someone in their early twenties—

DOMINIC: —A twenty-one-year-old veteran!

JENNY: Yeah, I know, but in that period of a few years in that industry you do have time to grow jaded and clock up a lot of bad experiences. So originally I had it in mind that she’d be telling the story as a memoir to her ghostwriter, before I realised that breaking the fourth wall like that is really annoying for the reader. So I have her looking back.

DOMINIC: It’s almost like an autobiography.

JENNY: Oh yeah, yeah. I love those memoirs, so I almost set out to write one, in a jealous, I-haven’t-had-that-experience kind of way.

DOMINIC: And is that a bit of the motivation behind the book? Because I always wanted to be in a band – I’d spend all the time in my bedroom trying to learn how to play the bass… it’s not that hard to play the bass…

JENNY: Surely!

DOMINIC: I certainly fantasised about the name of the first album, that sort of thing. Was there a bit of that for you, writing Cherry Bomb?

JENNY: Of course. When I was in my first band, I was way more interested in writing the liner notes of our never-to-be-released album than doing the hard work. But really it comes out of the fact that I’ve been a music journalist for 20 years and I feel like I’m a bit of an amateur psychologist. I’m not a very combative journalist, I’m more about trying to get into people’s heads. So I’m always diagnosing people in my head, thinking: codependent; narcissist; borderline personality… but you can’t say these things, so instead I’ve been storing them up as observations. And finally I found the format in which I could say it.

DOMINIC: It’s a strange thing, because we fall in love with these three-minute creations and we want to go and see the performers, but then in a sense we feel that we have a certain ownership of the person’s life. What happens when they’re NOT doing that three-minute song? There’s almost a disconnect between the exhilaration of the music and then what goes into producing it, which can lead to some quite damaged people.

JENNY: It goes back to what I was saying at the beginning: can you afford to fix what’s wrong with you if you’re known for writing these Bukowski-like vignettes of sorrow, can you go to rehab and sort yourself out? Probably not.

DOMINIC: Even for Coldplay, a fairly vanilla kind of band, the big break-up album post Gwyneth got extra interest. We all want to know which one is about Gwyneth and how that feels. It’s almost perverse.

JENNY: You’re right – ownership is the word. It must be incredibly difficult, particularly in Australia. If you’re an artist who has reached a certain level of fame there’s no escape really. You’re on the same tour circuit over and over, and the same people are going to see you at the bar after the show.

DOMINIC: Australian celebrities, it’s quite funny – they can only get so big in Australia.

JENNY: It’s not funny, it’s terrible! I feel so bad for certain people.

DOMINIC: You’ve set the novel in part in Kings Cross, so if someone got off the plane and had never been to Australia before, they could orient themselves pretty well. But you then take them to America, which is this fabled land where everyone wants to try and crack it.

JENNY: And Tamworth! I was looking at the career path of somebody who would have signed that size deal and where it would have logically have taken them – and that was the structure of my book; they start off in the dives of Sydney and wind up playing a massive charity concert. I thought, what would the points be between there? And more than likely you’re going to go to London, Berlin or LA and be stationed there for a bit, playing showcases.

DOMINIC: It did all feel familiar. Everything happened to The Dolls reminded me of talking to musicians and hearing about what goes on off stage. And alcohol plays a huge part. We were talking about the importance of keeping people damaged and it’s almost like alcohol is the means as to how that occurs.

JENNY: I think there’s a fear that if you give up something like that then you might lose your identity.

DOMINIC: And your creative edge.

JENNY: And your creative edge. And if you are on the tortured genius side of things, there may be some underlying mental disorder, for want of a better term, and what happens if you stop damping that down?

DOMINIC: The final thing I wanted to ask you about is the role of fans, which is a really interesting one, because there’s adulation but then there’s a degree of symbiosis as well. Bands need their fans.

JENNY: I gave the girls two very different viewpoints on this. I made Nina very uncomfortable with meet and greets and interactions on social media, and I made Rose thrive on it. Partly that’s your simple introvert/extrovert personality. I personally would find it extremely difficult! I’ve seen people who may be ‘out there’ on stage, but afterwards when they’re literally just trying to get from the dressing-room to the door to leave, they get backed into a corner, almost pressed into the wall, their eyes searching desperately for the door. It’s painful to see; you think, god, haven’t they given enough?

DOMINIC: It is funny that the music industry takes these geniuses who enjoy toiling away on their own on something amazing, and then they’re thrust into the spotlight and in a sense it’s the worst possible thing you could do to them.

JENNY: Yeah, it’s a conundrum. And that’s when, of course, you need the alcohol again, to be able to cope. And so whenever Nina’s got to talk to the media or fans, she’ll always have a miniature of Smirnoff on her. To cope.

DOMINIC: We’ve all seen people like that. Well, it’s a morally complex read, but certainly a very entertaining one as well. This book should probably be given out to anyone who’s considering starting a band in 2014 – it’s an instructional manual.